I wrote a travel guide to Hong Kong. Then everything changed

About this time in 2019, I was enjoying the privilege of staying at Hong Kong’s then newly opened Rosewood. This astonishing hotel, in the neon-lit retail hive of Tsim Sha Tsui, on Hong Kong’s Kowloon side, takes up 43 floors of an also then-new 65-storey building, a glittering harbourside monolith with a brilliant sun-reflective metallic finish.

With a big sweeping waterfront driveway, sartorially suited staff and, most special of all, a lobby gallery purpose-built to house Indian artist Bharti Kher’s magnificent life-sized elephant, the Rosewood instantly became the crowning glory of the city’s luxury hotel scene.

This unforgettable stay was part of a media trip for the opening of the hotel, but it also served as the final dot-the-‘i’s’ and cross-the-‘t’s’ research trip for my travel book Hong Kong Pocket Precincts. I had been working on this curated guide to the city’s cultural hangouts, shops, bars and eateries for the best part of a year, so I felt deserving of the stay. In the morning I’d be pounding the pavements exploring the characteristic old suburbs of Sheung Wan and Sham Shui Po, in the afternoon I’d be imbibing ridiculously good cocktails at the hotel’s Manor Club (an executive lounge sporting a billiards table), or doing laps in the sixth-floor infinity-edged swimming pool.

Hong Kong Pocket Precincts would be my second book about this city, another labour of love and a homage to the place I had previously called home for six years – where I had arrived fresh to start a new life after getting married, and where my first child was born. Though I had moved back to Melbourne five years earlier, in the intervening years I couldn’t get Hong Kong out of my system. On any given opportunity, I’d return to feel the rush of arriving at Hong Kong airport, the buzz of being in Central among the ding ding of trundling trams, the high of being among the whole glorious cacophony of what was then often referred to as ‘Asia’s world city’.

If I had known then what I know now, I might have cherished that stay just a little bit more.

In April 2019, two weeks after I departed, the city’s now-infamous protests kicked off. The rallying populace was objecting to proposed legislative amendments that would have allowed for extradition to mainland China. The situation pretty much went downhill from there.

By June that same year, one of the largest mass rallies ever seen in Hong Kong, a city I’d known for its law-abiding and peaceful populace, flashed across screens around the world. Hundreds of thousands of people marched through the wide streets of Causeway Bay, a neighbourhood I knew better for its plastic chairs and street-side bowls of noodles. Such a political scene had not been witnessed since the British Handover in 1997.

Come August peaceful protests and airport sit-ins were punctuated by increasing bouts of violence including the police storming of an MTR train station. By early September, notwithstanding the government’s overturning of the extradition order, widespread civilian unrest continued with protests breaking out across the city and further demands being made on a government considered increasingly pro-Beijing.

With the Australian government’s official warning against travelling to Hong Kong, the handful of stories I had been commissioned to write on Rosewood’s new opening were put on hold. Not long after they were summarily ‘killed’, as is the newspaper parlance. Regardless, under this dark cloud of doubt, I continued to write Hong Kong Pocket Precincts, focusing on the recent past and, uncomfortably but optimistically, ignoring what the future might hold.

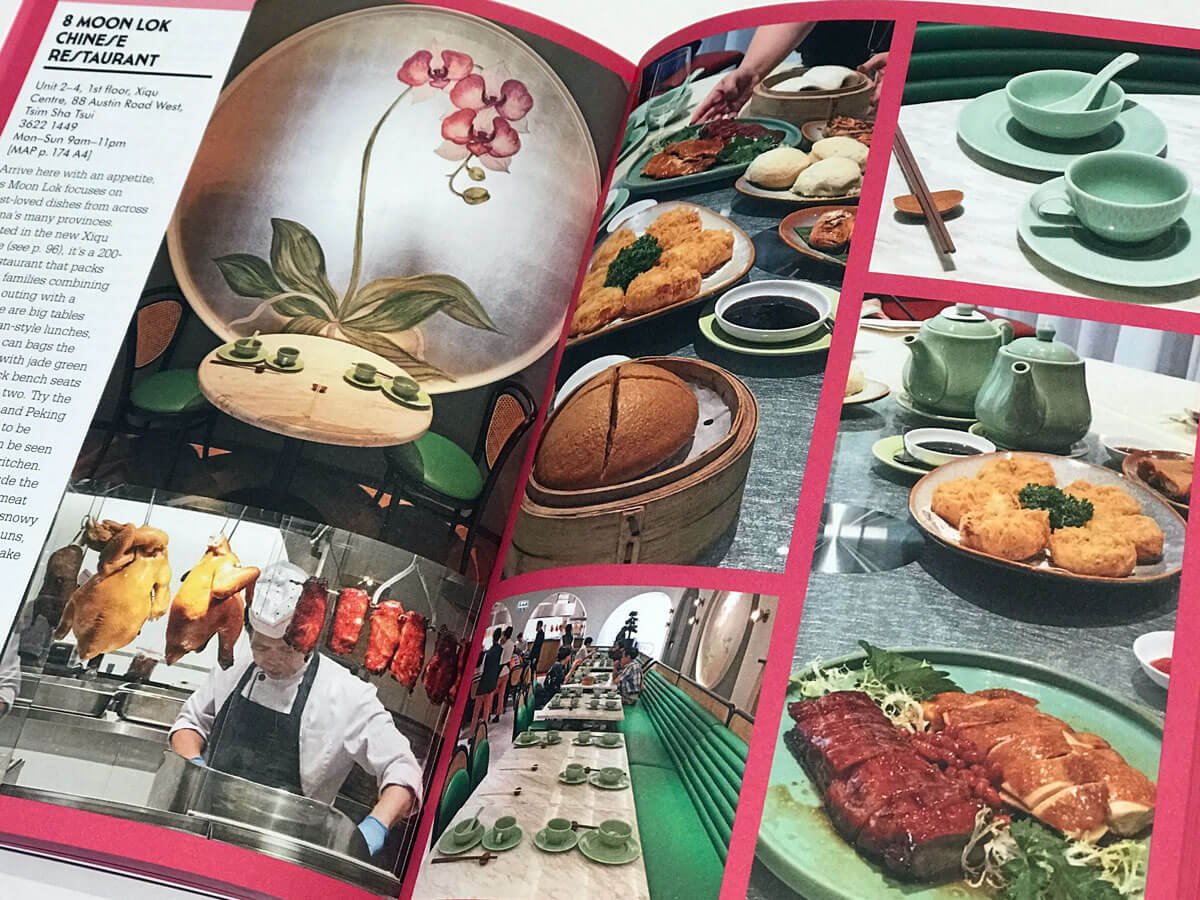

There had been at least two significant new cultural openings in Hong Kong that past year and I was excited about including them. The first was the incredible new Xiqu (Chinese Opera) Theatre, in the then still unfinished West Kowloon Cultural District. This extravagant complex, with a grand theatre to accommodate 1073 opera fans, had been attracting attention for its mind-bending architecture, with a warped and wavy exterior covered in metal scales inspired by Chinese lanterns.

The other big opening was across Victoria Harbour in Hong Kong Island’s Soho. The exceptional Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts, an ambitious 10-year, $3.8 billion vision, had taken over the hillside Central Police Compound, a heritage complex with 16 buildings, including former prison cells and barracks repurposed as theatres, galleries, studios and eateries. Styled as an urban lifestyle oasis, the Centre’s buildings and open spaces were thoughtfully connected to encourage meandering and lingering.

But it seemed the more I wrote about the city that I idolised, the more the headlines were telling a different story.

Chinese National Day, on October 1, dramatically escalated the protests along with a new anti-mask law introduced (and subsequently overturned) so authorities could identify protestors more easily. The citywide upheaval continued through November when protestors blockaded streets and threw Molotov cocktails at police, who responded with tear gas and water cannons. The situation sank to a new low when protestors were arrested in their homes and when police shot a student protestor at point-blank range. I could hardly recognise the Hong Kong that I once knew.

In my book’s travel tips section, my editor proposed including a paragraph about safety and caution in the current social/political situation. “We can say ‘at the time of writing’ so it doesn’t date the book”, she said hopefully.

Similarly, in the acknowledgments I wrote of my hope that “by the time this book goes to print, the political environment has settled, and the city remains the peaceful place I know it to be.”

I submitted the manuscript to my publisher and it went to the printers soon after.

For a short time during December, the crisis in Hong Kong looked like it was easing with the expectation that some demands on the government would be met. Could this be the tail end of this dramatic period in Hong Kong’s history? Far from it. Certainly, come January and February 2020, the headlines had gone quiet, but we know why in retrospect. The media had turned its attention to COVID-19.

When my pretty little guidebook with Chinese lanterns on the cover (styled to fit in a handbag and light enough for a carry-on suitcase) launched in April 2020, the whole world was trying to get a grip on the first weeks of the pandemic. All our lives were about to go into freefall.

So here we are, three years after the book’s publication and four years after that last trip to Hong Kong. The city, now technically known as China, has finally reopened to tourists. It has endured through political and social upheaval, and one of the world’s longest and hardest lockdowns, lasting on and off for close to three years. I miss it all the more.

In tourist terms too there’s been plenty of change. The stupendously long-awaited West Kowloon Cultural District has finally opened, and within it, M+, a world-class art gallery, and the Hong Kong Palace Museum, packed with art and cultural treasures from Beijing’s Palace Museum.

The Peak Tram has had a major facelift, with larger panoramic windows to take in the city’s intoxicating skyline. Hong Kong Disney has a new ‘Castle of Magical Dreams’ and Water World has opened at Ocean Park. The St Regis hotel sounds like it might be in competition with Rosewood for luxury stays.

But some things haven’t changed. I flick through my book hungry for old haunts, nostalgic for the dumpling joints, pungent street markets, and litany of cool bars and boutique shops hidden among the sloping cobbled streets.

To get a sense of the vibe on the ground, and to know whether my book has lasted the distance, I post on Instagram.

“I’d take some more copies,” says one stockist. “The city is bouncing back. So hard to book tables again these days!”

Another says: “It’s such a great book – and still relevant! The city feels alive again now – seems to be picking up quickly.”

The heartening response makes me more excited to get back. As I nut out my itinerary, I note that in my absence Rosewood has opened its new Asaya Spa. I’ll have to head back to the hotel to check it out, naturally.

Hong Kong Pocket Precincts, by Penny Watson, is published by Hardie Grant and is available online and in many good bookstores.